Biographical notes

from Baker Awards Nomination bio:

Bill Shimek was born in

That period ended in 1985 when he returned to

Shimek has seen phases where his work has sold feverishly,

and periods of scant commercial success. Through it all he has remained

prolific; when he is about to finish one piece, he is already planning the next.

His work has been shown by the

From

The Baltimore Sun:

Exhibition: Bill Shimek 'never learned the rules' of art, but the American Visionary Art Museum doesn't seem to mind.

By Lane Harvey Brown

Sun Staff

Originally published August 24, 2003

The hand-hewn coop sits on one side of painter Bill Shimek's Darlington studio, flanked by richly colored canvases, a wood stove and shelves of acrylic paint - a fitting reminder perhaps of how inspiration often springs from simple sources.

Shimek didn't pick up a paintbrush until he was 30. But when you ask him how he knew he had it in him to be a painter, it's another chicken coop he recalls, one he built in junior high school.

"I've always liked making things," he said one recent afternoon, sitting on a stool in front of a tall window framed by multihued paint jars and the colorfully splattered table where he works.

To Shimek, art is another thing he likes to make, and the 56-year-old has accumulated a range of credits: coops, canvases, furniture, shadow boxes, clocks and the very rooms around him in the 19th-century mill he restored on Deer Creek, in northern Harford County.

Two of Shimek's works are part of a show called Community Voices, which opens today at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, a local perspective on the museum's yearlong exhibit on addictions.

The part-time District Court commissioner and accomplished woodworker says his approach to painting is unfettered by the concerns of formal training.

"I never learned the rules and I never learned how hard it is," Shimek said, smiling.

"I think it has been easier for me, being able to make my own rules."

The show's jury was struck by his work, said Marcia Semmes, the museum's director of development.

Shimek's pieces in the exhibit are large totems in bright colors, which contrast with the serious theme of the show, Semmes said.

"It's an interesting juxtaposition," she said. His style "makes you take a pause to think about it."

Shimek's "Monkey on My Back" features a monkey with a man on its back, while "Don't Ask, Don't Tell, Don't Peek" captures three men reminiscent of monkeys seeing, hearing and saying no evil.

He said that he had created the totems before the show, but that their ideas fit the theme nicely. Other totems can be seen around his mill, stacking not-quite-human or animal forms atop one another.

Shimek said the blurring of the lines is to make a point. "Too many people don't recognize humans as animals and don't recognize animals as thinking beings," he said.

Shimek didn't consider painting as a boy and teen in his working-class Perry Hall neighborhood in the late 1950s, where the family lived until moving to Bel Air when Shimek was in high school. "Where I grew up, art was for girls," he said.

It wasn't until after he had graduated from law school and had practiced for several years that he tried an evening painting class. He put brush to canvas and liked what he saw.

"I was just really surprised that I could do that, and I just kept doing it," he said.

He gets a thorough critique now and then from fellow Bel Air High classmate, Judith Simons, who also lives in Harford County. She told him about the visionary arts show; she also has a work in it - a multimedia work titled "WTLS," a shrine to people she knows who lost years of their lives to addictions.

She said she and Shimek exchange comments about their work; he sometimes sends her photos of his works in progress via e-mail.

But for the most part, she said, he hangs back from too much art criticism. "He doesn't read about art, doesn't want to be influenced," she said.

In Shimek's kitchen hangs a study of cattails in blues and other cool hues from a pond at Simons' home. The kitchen and living room are built with half-walls, creating an open and airy feel. He said he worked for nine years to restore Noble's Mill, built in 1854 - and said he would never have done it if he had known what he was getting into.

Monroe Duke, who sold the mill to Shimek in the late 1980s, said he has been pleased to watch his neighbor's work.

Shimek kept all the original machinery intact, building around it, right down to his loft bed in the studio, which sits over a seed separator.

"He has done an extensive job," Duke said, noting the carpentry, painting, roofing and masonry work that was needed on the three-story building. "Bill has a lot of imagination, and he is energetic."

Shimek's work at the court keeps him on call nights and weekends, he said, but his painting schedule remains fluid. "If I start on something I'm excited about, I sort of forget about the time," he said.

He reaches into his little chick coop, scooping up one among a handful of chicks, noting from their new feathers that they are almost old enough to move outside with his seven hens.

On the wall behind him in his studio, as in the hallway, the living room and the kitchen, his canvases line the walls. Many are progressions of the same themes. They are bold flowers, landscapes and portraits, especially of a dark-haired woman he has painted for more than 20 years. The curves of her face and body appear in many scenes.

Finding more buyers would be nice, he said, gazing at his many works, and maybe this show will be good for that. But, then again, he has never cared much for the business end of art.

"I'll just collect my own art until there's somebody to help me sell it," he said.

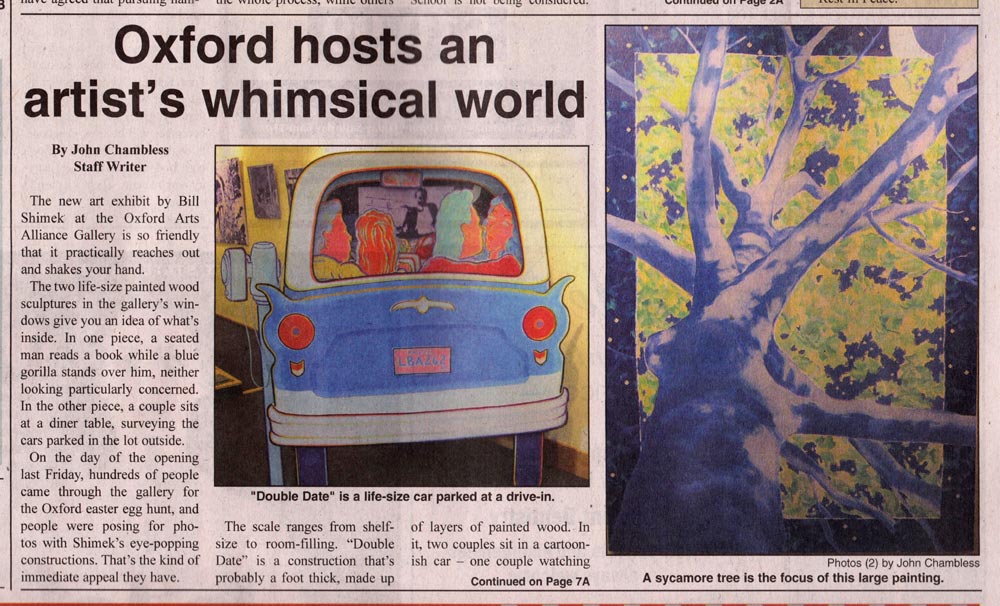

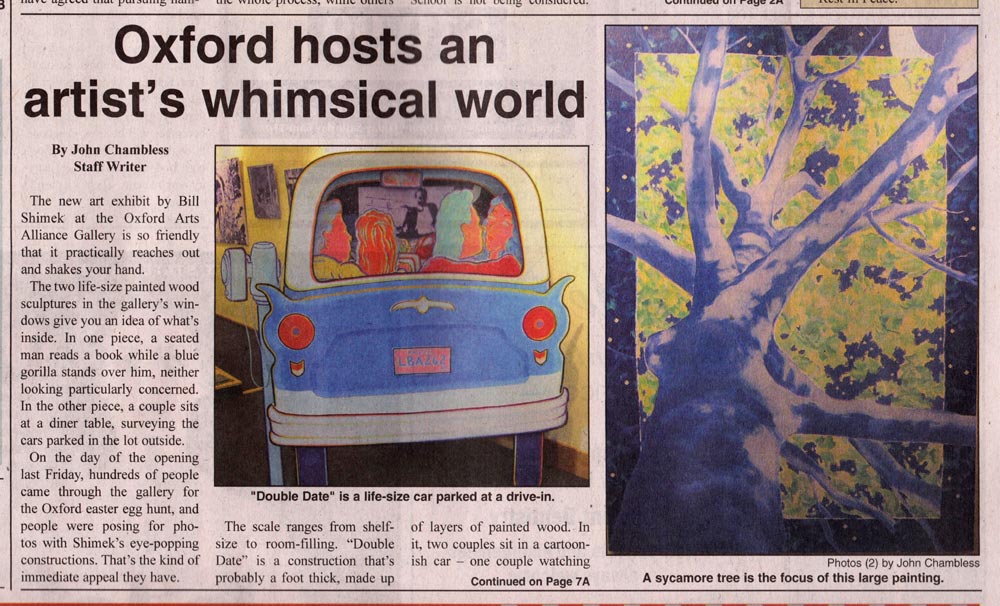

From The Chester County Press (PA), 4/11/12: